Why I, A Former Nubank Skeptic, Am Now Looking For Shares To Triple

How Nu left its FinTech and neobank competitors in the dust, and a deep look into its future growth prospects

Summary

Nu Holdings has gone from start-up to LatAm's most valuable financial institution in a decade.

I was initially skeptical of Nu for a variety of reasons. I explain why I missed Nu in 2023 and how it won me over today.

Nu is even more profitable than you think; its investment in new growth markets is diluting the insane 60% ROE it is generating off the core Brazilian business.

I see upside to $30-$45/share by 2030 compared to my initial recommendation price of $11 earlier this quarter.

Quick thoughts on FX and near-term factors going into today's Q1 earnings print.

Nu Holdings (NYSE:NU), which operates Nu Bank, is the world's largest non-Chinese neo-banking institution.

With approximately 120 million customers today, Nu should overtake Santander (about 175 million) for the title of largest western bank by customer base within the next few years.

It's been a meteoric rise.

Nu launched in 2014. In just a decade, it's already become the most valuable financial institution in Latin America. And there's no signs of slowing down.

Nu is a sin of omission on my part, which I rectified earlier this year. I looked at Nu in 2023 but initially passed on it. I'll explain why I missed this company then, and in doing so explain how Nu stands out from the see of other Neobanking and FinTech startups.

How I Overlooked Nu Initially

When I looked at the bank in 2023 it was still merely breaking even. Its net income had been steady around -$150 million annually dating back to the onset of the pandemic. Here's Nu's revenues vs. net income from IPO through mid-2023:

There are many such cases in FinTech land where companies grow topline quickly by making risky loans and/or underpricing financial services below market rates to grab market share. If I see revenues of a financial institution soaring without any movement in profitability, I get nervous.

For another thing, I hold Brazilian management teams in fairly low esteem. I knew that Nu's founder was Colombian, not Brazilian, but I assumed that the company was still fairly Brazilian in terms of its operational DNA and management philosophy.

I read a corporate biography, Nubank: Purple Revolution earlier this year that shed a great deal of light on the company's founding and early days. It turns out that the company is not very Brazilian at all, and has far more U.S. managerial influence than that of Brazil. This was a decisive factor in making me be willing to invest in Nu despite my prior misgivings.

Another point of concern for me in 2023 was Nu highlighting new cryptocurrency trading products. Almost without fail, when U.S. companies pivot to crypto, it's because they don't have any momentum with their actual core business. Square/Block/XYZ/whatever Jack Dorsey names it next,is the classic example of this, but I could list half a dozen such cases here. I'm allergic to FinTechs peddling crypto, so Nu struck me wrong there. But, thankfully, fast forwarding to today -- it looks like crypto has turned out to be just one of a zillion business lines for Nu and they aren't wasting serious balance sheet capacity or management attention on crypto. (On a related note, Nu also has a buy now, pay later product, and I also instinctively get a vomit reflex thinking about BNPL).

Additionally, in 2023, I failed to appreciate just how broad their customer base had already become. There's a joke in Brazil about Nu's stinginess, with the joke poking fun of the bank's reputation for offering people mere $25 credit limits. That's a bit of hyperbole, but that's directionally accurate; Nu tends to offer tiny credit limits to new customers.

Between Nu's history of unprofitability up through 2023 and its seeming ability to only attract customers of limited financial means, I figured it would take a while for Nu to scale up to strong profitability.

The established Brazilian banks (along with markets like Colombia and Mexico) tend to prefer to do business with rich people and offer limited services to middle and lower-class customers. It makes sense that a new competitor could come in and gain millions of customers overnight with a no-fee debit or credit card offering. However, traditionally, there's a reason why most LatAm banks didn't want these lower-class people as customers.

---

I present this self-assessment of my past thinking because I imagine other potential readers may have similar reservations about Nu.

It's also more powerful when people have a "Road to Damascus" moment and transform from being a skeptic to a convert to an idea.

You can find plenty of people online who are bullish on Nu. But, by and large, they are also bullish on stuff like Carvana, Microstrategy, Super Micro Computer, Affirm, Upstart, GameStop, and other companies of exceptionally dubious fundamental standing. Most of the bulls on Nu are pure growth-at-any-cost investors and don't spend much time focused on items such as credit quality or regulatory risk.

By contrast, I've been a longtime shareholder in many traditional LatAm banking institutions. I'm a well-known skeptic of FinTechs and have written negatively, at length, about companies like SoFi, Affirm, and Block. I was prepared to write Nu off as another fad or "flavor of the month" company in that lane. But that'd be a wholly mistaken conclusion.

I'm now a full-throated believer in Nu and have established a significant position in the company's stock and call options.

Behind Nu's Meteoric Rise

Nu Bank's incredible trajectory was possible due to its management team. A Colombian, David Velez, came up with the concept for the bank. He enlisted two co-founders once he had the business model in mind; one of these was an American with a consulting background in the finance space, the other was a Brazilian that had headed credit card issuance for a competitor previously.

Velez grew up in Colombia and Costa Rica but went to the U.S. to study. He got both a degree and then an MBA from Stanford. He used that as a springboard to get into the investment industry, working for Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. In turn, Sequoia deployed him to Brazil to set up a local office there.

This was a challenge for Velez as he didn't previously speak business-level Portuguese or have much experience in that market.

This is an important distinction, as Velez was not familiar with Brazilian financial culture and approached that market with fresh eyes. Instead of being accustomed to instead "business as usual" in Brazil, he approached it as a skeptical U.S.-educated outsider.

For example, when working in Brazil, he found it exceedingly difficult to get access to a simple bank account. It took Velez was it taking weeks and countless time meeting with different bank employees to get anything set up. That gave him the idea of trying to disrupt the market.

In addition, Brazil's interest rates are far higher than in Velez's native Colombia. In Colombia, we have anti-usury laws which cap (legal) interest rates at somewhat normal levels. If you want exceedingly high interest rate loans, you have to go to the black market or informal lenders.

By contrast, in Brazil, the average credit card interest rate runs above 200% per year. You read that right. Personal loans also run at nearly 100% a year (though they are typically quoted at about 6%/month to sound more palatable to consumers).

Velez saw the opportunity to launch a bank that would be user-friendly and not have huge costs for simple things like having an open savings account or having a debit card while charging somewhat lower rates on consumer credit.

--

Velez and his two co-founders launched Nubank with a simple no-fee Mastercard credit card. This was the first fee-free card available in Brazil.

The original idea was to fund Nubank primarily by collecting interchange fees on transactions. Of note, Nubank almost ran out of money right at launch, and Velez operated the company with a shoestring budget out of a house. Not your typical Silicon Valley FinTech spending lavishly on fluff before becoming successful.

Nu used the popularity of the initial credit card product to launch its debit card, savings products, and start transitioning toward being a full-service bank.

It also began to hold a much larger loan book of credit card receivables rather than primarily operating credit cards as a transaction method and collecting fees. More on this distinction in a bit...

Nu also continued to roll out ancillary products. It bought a brokerage firm and integrated that into its app. It began to offer life insurance products through a partnership with Chubb, and has more recently began working on other insurance verticals like auto. Nu began to offer cryptocurrency holding and trading. It also went into lending against government payments such as pensions, which is a huge market in Brazil that is still primarily controlled by brick-and-mortar loan outlets.

Today, nearly 30% of Brazilian adults consider Nu to be their primary bank and nearly half of Brazilians have at least one account with Nu in one form or another.

Within Brazil, Nu is already a full-fledged bank. It's not just a point solution for one particular offering. This is a key distinctive feature compared to most FinTechs. Nu isn't just a credit card or a way to transfer money or get personal loans; it's everything at once but without the monthly fees associated with traditional Brazilian banks.

Over the past five years or so, Nu has used its original success in Brazil as a springboard to go into other markets. Specifically, it has targeted Mexico -- a natural choice as the second-largest market in LatAm. And, unsurprisingly, Nu has also launched in Colombia, Velez's native country. Mexico and Colombia combined have nearly the same population and GDP as Brazil, meaning that -- with similar market penetration -- Nu can double the size of its business.

Nu also intends to launch in other markets over the next five years. This could include smaller LatAm countries like Chile, Peru, or Argentina. And Velez has spoken about potentially expanding outside of LatAm as well.

I doubt Spain would be a top priority as that country's economy is exceptionally stagnant and there are higher regulatory barriers. The U.S. would be a logical expansion target in one way, as its 65 million Hispanic-Americans are generally not well-served by the large English-language money center banks. That said, the U.S. has low interest rates on credit products and Nu would take a big hit to its ROE as compared to doing business in LatAm. I don't assign much value to future growth possibilities outside of LatAm -- that's more icing on the cake if anything works there but the market in Brazil/Mexico/Colombia alone is plenty big for NU stock to be a multibagger from here.

--

Looking at Nu's combined financial metrics undersells just how profitable the bank is today.

Consider that it took Nu about seven years to get from launch to meaningful profitability in the Brazilian market specifically. Mexico and Colombia are both not yet significantly profitable for Nu, but that's to be expected as it launched in both of those more recently.

We will almost undoubtedly see a similar tipping point where Mexico and Colombia go strongly into the black for Nu and its overall profitability levels soar.

To update the chart from above, here is Nu's (corporate level) revenues and net income from IPO through today, rather than cut off in 2023:

The company is, incredibly enough, turning almost 25% of every real and peso that comes through the door into net income. And that's with two of its three operating countries still being far from mature businesses.

If you look at just Brazil in isolation, now that the market has started to mature and ripen for Nu, you see insane levels of success. Nu is printing at 60% return on equity ("ROE") figure in its Brazilian subsidiary. (The overall Nu organization was "just" a 28% ROE in 2024, showing how much Mexico and Colombia are still diluting the more advanced Brazilian business)

This is, funnily enough, one reason I passed on Nu in 2023. At the time, I saw a bullish report citing Nu's then-nearly 50% ROE in Brazil and I assumed it was a misprint, someone had calculated the FX wrong, or it was an outright fraud.

You simply don't earn 50%+ ROEs in banking. Nu is earning a much higher return on its capital than Alphabet or Meta does.

How on Earth does a bank make a 60% ROE?

The large U.S. banks like JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs can make 15% in a good year. In Latin America, the traditional mainline banks can make 20% ROEs at the top of an economic cycle if everything is going well. Maybe you can squeeze out 22-23% ROEs in peak economic boom conditions in a less competitive banking market like Colombia or Peru.

But no bank, LatAm or otherwise, is printing 60% ROEs.

Using my bank valuation rule of 10, you'd expect fair value for a 10% ROE bank to be 1.0x book value. A 15% ROE would allow you to pay 1.5x book value, a healthy premium, for that strong performance. A weak bank with say, just a 7% ROE should trade around 0.7x book value.

A 60% ROE, by contrast, would allow for paying 6x book value as fair value -- almost rendering the P/B metric pointless within the context of bank valuation (for what it's worth, my initial Nu recommendation in March was at just under 7x book, not far from my framework even in this outlier case).

I want to reiterate here that traditional LatAm banks are also (often) attractive because you get to buy high ROE franchises at discounts to book value, such as recently when Colombian banks with 15% mid-cycle ROEs were selling well under book value. You make a ton of money owning those, particularly as they are known for paying out double digit dividend yields while you own them. Good stuff.

That said, buying one of the largest banks in the hemisphere with a 60% ROE and 40% top-line growth can also be a good way to make money.

Why Nu Has Achieved Ridiculous Levels Of Profitability

Rock bottom operating costs. That's the magic trick here.

Most banks, both in the United States and in emerging markets, use legacy technology systems. In some cases, we're still talking mainframes. Or systems that have been partially modernized but are now clunky and don't operate well across departments. I spoke to one former IT guy at State Street who related that part of that bank's core IT system was being upgraded for more than eight years before work was finally complete. That sounds fun!

Brazil is no exception to this. In fact, in some ways it's worse. Brazil has onerous labor protection laws meaning that it's hard to fire employees and there's a ton of friction in terms of trying to get capable staffing. Result? You have a lot of older employees that don't understand or have interest in learning new tech solutions. Even by LatAm standards, Brazilian banks are behind the times and thus have higher operating costs and limited ability to deploy new technology.

Combine that with the huge branch networks, and Brazilian banks have surprisingly high operating costs. (The labor protections mean that it costs way more to hire people such as bank tellers and security guards for a Brazilian bank as opposed to a Colombian bank).

Bottom line? By some estimates, Nu bank can service its average Brazilian client at 1/11th (!) the cost of a normal Brazilian bank.

That figure is closer to 1/7 of the cost of to service a customer for Nu in Colombia and Mexico compared to their established traditional banks.

To put it another way, Nu can, on average, service each customer account for less than $1/month.

We see how this plays out when we turn to the revenue side of the equation. For full-year 2023, Nu Bank earned just over $10/month per Brazilian customer which badly trailed the incumbent large Brazilian banks who earned about $45 per customer on average. (The median legal Brazilian wage is around $500/month and many people work informally for much less, showing how limited the market is for big banks that are collecting $45/month in revenues per average user).

Since Nu can service people at a tenth of the cost of the incumbents, it can reach the entire Brazilian middle class who simply didn't have enough money to be profitable clients of the legacy Brazilian financial institutions.

Nu built a whole new banking operating system using the latest technology with knowhow from its U.S. educated developers with a focus on being native to apps rather than at bank branches or through PCs. We have seen very few "from the ground up" entirely new bank operating systems for decades now -- and none of note in Latam -- meaning that Nu has a large and scalable competitive advantage here.

--

Over time, Nu expects its revenue per user to rise as more of its clients go beyond just using debit/credit cards and get comfortable with using Nu for insurance, brokerage, personal loans, etc. That said, I don't think Nu will get anywhere near the same revenue per customer as the traditional Brazilian banks -- nor will it have to. There's a great business to be had collecting a modest sum of money from 100 million customers, and there's another great business in offering much better service to 10 million wealthy customers. Both banking business models can coexist peacefully.

Nu has a small offering in the high-net-worth space, more of an American Express styled rewards card rather than mass market fee-free offering. However, uptake has been low and rich people still by-and-large look down on Nu as a bank for the proles. But so be it; Nu doesn't need wealthy customers to succeed.

Another unique point of the Brazilian market in particular is that the mortgage market is quite small due to the historical challenges in enforcing deeds and serving foreclosures within Brazil's lackluster legal system. As a result, people have a far higher percentage of their total credit exposure via sky-high interest rate credit cards and personal loans. Nu bank can undercut those existing credit card interest rates meaningfully to build out its loan book without having to tie up a lot of capital in lower ROE vehicle or home loans.

Nu bank is also not a meaningful player on the commercial or investment banking side of things. But again, that's not important. It is by far the lowest-cost retail bank out there, and there's plenty of white space getting the lower class people into the banking system. As recently as a couple of years ago, for example, fewer than 10% of Colombians had a checking account. The unserved market is tremendous.

Credit Risk & Loan Underwriting

But Ian, isn't Nu going to blow itself up lending to these poorer people with no credit history?

Good question. This was one of my concerns in 2023 when I first kicked the tires here. Peer MercadoLibre is known for its loose lending standards and aggressive underwriting of questionable customers. Since Nu was growing faster than MercadoLibre, I kind of assumed that it had to be taking shortcuts on credit quality to pump up the top-line growth. But that was a mistaken view on my part.

As it would turn out, however, Nu hired one of Capital One's top people to help build out its own risk management department right from the time of launch. That wasn't just a one-time thing, either. Nu has continued to routinely poach top Capital One risk department folks to build out its own underwriting capabilities.

Capital One, of course, has become a dominant player in U.S. credit cards and been an absolute home run long-term investment, almost tripling the returns of the S&P 500 over the past 30 years despite the 2008 financial crisis:

It's rather encouraging to see that Nu is building out its risk management department with Capital One rather than Brazilian risk management DNA.

It's worth elaborating on how this plays out in practice.

Capital One is known for its "low and grow" philosophy. It will extend a credit card with a tiny limit, usually $500, to just about any U.S. citizen even if they have no credit history whatsoever. A $500 credit limit sounds laughably small to your average Citibank or Wells Fargo customer. In the same way that people mocked Nu for its silly $25 credit limit cards in Brazil five years ago.

Over time, however, Capital One builds up large amounts of data on its customers and can algorithmically predict which ones can handle higher limits and which should be kept at $500. Over time, Capital One has built up one of the largest credit card loan books in the U.S. (#4 player, about 11% share) despite having small average account balances and being known for its risk-averse underwriting standards.

Interestingly, Capital One operates far fewer branches and has less overhead than most of its big U.S. banking peers. Due to its business model, it doesn't have to chase primarily large borrowers, allowing its differentiated low-and-grow model to prosper. Nu has taken this to an even greater extreme, operating no branches whatsoever while using Capital One's core lending strategy to the fullest.

Arguably, this has even higher upside for Nu, long-term, because of the diversity of its product lines. Nu is most adopted among younger consumers. An ideal customer is a new college graduate who has few financial resources and is at the start of their career. Nu is happy to open a fee-free credit card with a tiny limit since it costs them less than $1/month to service it. No traditional Brazilian bank would be in any great rush to do business with this hypothetical customer.

Over the next five or ten years, a fair number of these new college graduates will get promotions and start bringing in more serious money. Their Nu credit card has now had the limit raised from $25 to $500 due to past on-time payments. In addition, this consumer is now signing up for life insurance through Nu while starting to buy stocks on the Brazilian exchange through his or her Nu brokerage service.

In the Brazil of old, this customer simply wouldn't have had access to any Brazilian bank account until they were age 35 or 40. Now, Nu can sign them up early and then enjoy higher revenues per customer as they age up and obtain higher spending power.

What's really impressed me is how quickly Nu bank has been able to scale up the amount of business it does with his customers on average. When I looked at this business in 2023, I assumed this would be a 5-10 year maturing process before their first customer cohorts starting to become real cash cows for Nu. But it's already happening at scale in 2025.

Pix: An Underrated Tailwind For Nu

There's a key element here that helped spur this sudden growth. That would be Brazil's "Pix" (instant payment ecosystem) network. Launched in 2019, Pix is a system run by the Brazilian Central Bank to allow instantaneous low-cost payments and money transfers. Brazil's government was interested in rolling out Pix with the intention of reducing cash usage, thus allowing for more effective tax collection.

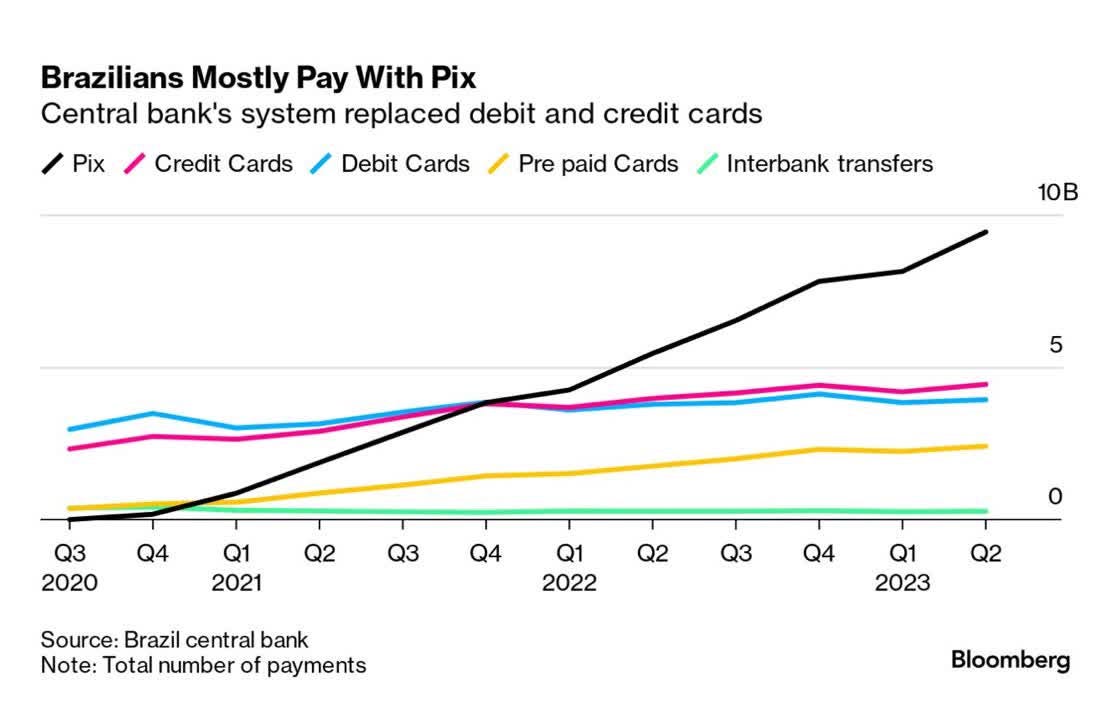

This was ideal timing, as the pandemic hit in 2020, causing people to want digital payments solutions anyway. Estimates suggest that cash usage has fallen by half in Brazil since Pix launched and Pix has quickly become the largest payments solution in the country, overtaking the entrenched players. Even by 2023, Pix had already surpassed the competition, to say nothing of where we are now in 2025. Notably, however, credit and debit card usage also continues to rise... the biggest loser here by far is cash:

I've seen some analysts refer to companies such as Pagseguro (NYSE:PAGS) as being the "next" or "cheaper" NU but this is an entirely spurious/errant comparison. The payments players were greatly harmed by Pix whereas it has been a boon for Nu.

Keep in mind Nu bank is an entirely digital bank. No branches. No ATMs. Much of a traditional bank's function is to provide cash services, either at branches or via ATMs.

Nu has no use for cash. As cash greatly diminishes in importance in Brazilian society, a key Nu structural disadvantage disappears.

While Pix was helping Nu by making the economy more digital/less-cash based, it also gave the company a second tailwind. Namely, Nu was the first bank in Brazil to allow customers to fund Pix transactions via credit cards. Meaning, you could use credit up to your limit to purchase goods or send people money via Pix.

As a result, Nu got a flood of signups to join its service from people who specifically wanted to link a credit card to Pix. Nu now has a much higher rate of people attaching their identification codes (phone number, e-mail address, whatever) for Pix to a Nu account than you would have expected based on Brazilian bank market share data at the time that Pix launched. This was the first real watershed moment where higher income people with existing bank accounts at a legacy financial institution started to switch their primary banking account over to Nu.

Pix may seem like an arcane detail. However, it's worth mentioning since I've seen some people mention it as a risk factor to Nu when it's not really one (yes, they might lose some interchange fees from fewer card transactions but they make this back and more from gaining new accounts tied to Pix plus financing Pix loans). And also, people keep trying to compare Nu to firms like Pagseguro when that's like comparing an apple to a cucumber.

But enough on Pix and the Brazilian market, let's turn to Mexico.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ian’s Insider Corner to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.