Weekend Digest #304: 11 Questions About Tariffs & The Market's Response

Exploring the world of opportunities post Liberation Day.

So, What Happened Last Week?

In last week's Digest, I wrote that the market was "sleepwalking right into the next tariff deadline". Incredibly enough, the VIX was still around 20 and we were barely seeing any new 52-week lows in the market. Everything was orderly despite the mounting risks.

Well, the sleepwalking has ended and everyone is wide awake now.

On Wednesday, President Trump proceeded with the across-the-board tariffs against all countries, at a 10% level, that had been expected prior to the announcement. Stocks initially popped on the seemingly benign outcome. But then we saw the poster board showing the country-by-country reciprocal tariffs including exceedingly high rates on many Southeast Asian countries, and markets started to tank.

As of this writing, there is little indication of any immediate change in plans around tariffs. There is talk of countries wanting to make deals and Vietnam and Cambodia in particular negotiating with the Trump team, but there hasn't been anything concrete enough to change sentiment.

Why Is This A Big Deal?

Some people are arguing that the tariffs aren't that big of a concern. After all, Trump did tariffs in 2018, the market panicked, and then it bounced back. Same thing this time around?

But it's a bad analogy. This chart shows why:

Tariffs bumped up from the high 1s to low 3s during the first Trump term. This left the total effective tariff rate below where they were in the early 1990s at the onset of NAFTA. That was an adjustment to policy, sure, but not any wholesale remaking of the world economic order.

By contrast, the new proposed set of tariffs would put the U.S. well above where tariffs peaked during the Great Depression. Tariffs rates shot up from about 13% to 20% thanks to the Smoot-Hawley tariffs instituted in 1930. These were, most economists believe, a significant contributing factor in transforming the economic downturn of 1929-30 into The Great Depression. If the currently proposed tariffs stick, we're making a move beyond how high tariffs went during the Great Depression and we'd be doing it off a base of almost no tariffs previously.

In addition, supply chains were much less globalized in the 1930s. It was difficult and time-consuming to send even basic goods across the Pacific Ocean and we didn't have the internet, high-speed telecommunications, and countless other such tools that make modern trade so easy and frictionless. Reversing global trade now will have more consequences and unintended impacts than it did in 1930.

Is The End Game Still Negotiated Deals?

Probably not.

"This is not a negotiation. This is a national emergency associated with chronic and massive trade deficits." - Trump trade chief Peter Navarro, last week.

I (and most analysts) were of the view that Trump was using tariffs threats as a stick to get people to the negotiating table.

I got worried about this view in February once Trump got concessions from Mexico and Canada and then ended up hitting them again with fresh tariffs in March. If this was all deal-making posturing, Trump should have taken the February concessions from Mexico and Canada, trumpeted his win, and moved on to trying to cut deals with China, SE Asian countries, Europe, etc.

Rather, this time around, it seems his team truly are committed to tariffs as a policy end in and of itself. They want to raise serious tax revenues from tariffs and view trade deficits as fundamentally unfair. They are creating an External Revenue Service; do you do that if you are planning on getting rid of all the tariffs tomorrow? Probably not.

---

The issue, though, is the question of an offramp.

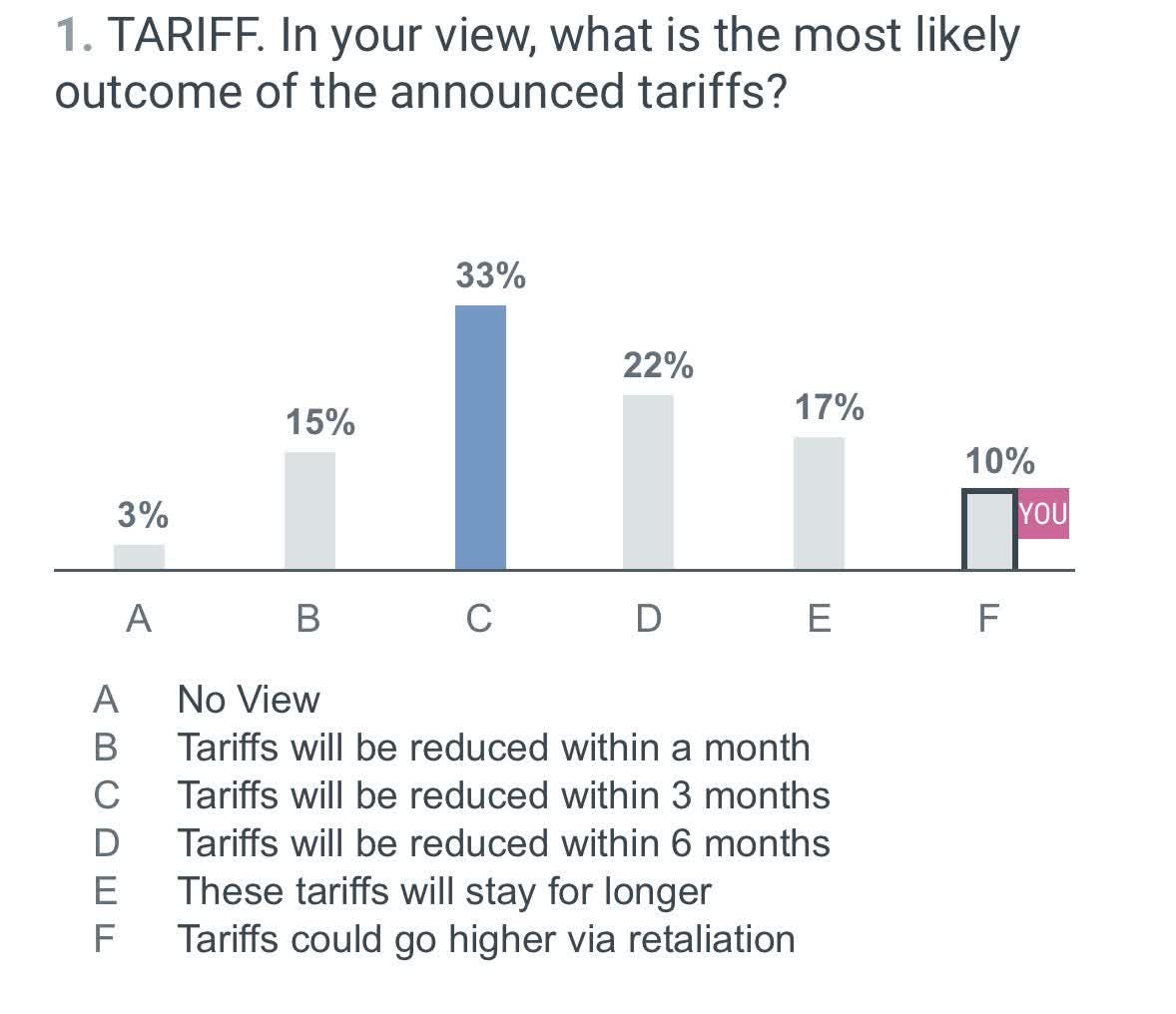

The market seems to still think that the tariffs will be short-lived. Here's a poll from a Goldman Sachs investor survey on Friday:

Source here. The "you" is the poll respondent, not your author.

One poll and limited sample size and all that, but 70% of professional investors still think the tariffs will be reduced within 6 months with the leading view being that they will be reduced by the end of Q2.

If we consider the possibility that Trump's team is serious and the tariffs are the new economic policy, not a negotiation tactic, arguably stocks still have a ways farther to fall.

What Happens If Musk Leaves The Administration?

There were reports on Friday that Elon Musk is possibly on the outs at the White House. Additionally, Musk has been tweeting much less over the past week. Musk took direct shots at Trump trade chief Peter Navarro, calling him an academic that has never built anything and didn't understand the realities of the tariff situation. And now, as of Monday morning, Musk is tweeting out anti-tariff videos from famed economist Milton Friedman.

Long story short, it seems Musk is against the White House's tariff policy, particularly since Musk recently stated he supports a zero-tariff trade zone with the EU. That is opposite of what Trump's latest policy would create. Finally, it's worth considering that Tesla shares are down by close to 50% from the recent highs. Musk's net worth is down by more than $100 billion year-to-date. Given Tesla's heavy reliance on China both for production and components for its electric vehicles, it's not hard to see Musk splitting with Trump publicly over this tariff policy.

The Kalshi real money betting market for whether Musk will quit DOGE by June is now up to 55%, suggesting slightly better than coin flip odds that his time heading that organization is soon drawing to a close.

If Musk quits or is forced out of DOGE, that would seem to be incrementally positive for stocks. Musk has operated with a brazen style at that organization, and you would have to imagine his replacement would take more measured steps. And that's assuming there was a replacement at all. So much of DOGE's mystique around young hackers and tech wizards fixing the system is reliant on Musk's branding to bring it all together.

I wouldn't be surprised if DOGE functionally stops being relevant once Musk is out of the picture. You'd expect defense companies like Lockheed Martin (NYSE:LMT) along with contractors such as CACI (NYSE:CACI) to catch a nice bid if and when Musk departs.

If Trump Reverses Course, Would Stocks V-Bottom?

Prior to the current tariff issue arising, analysts were forecasting roughly $270 in total S&P 500 earnings for this year, up from the $243 recorded in 2024. Slap a simple 20x P/E multiple on that and we should get an S&P 500 of 5,400. So stocks are slightly undervalued here, right?

I'd expect those earnings estimates to come down a fair bit over the next few weeks. Even if the tariffs got called off now, we've already significantly disrupted both supply chains and investment plans for this year.

As Molson Hart, an entrepreneur who manufactures toys in Texas, noted on Twitter this weekend:

"We placed a $50,000 order with our supplier overseas before the election in November 2024. At the time of ordering, there were no import taxes on the goods. By the time it arrived, a 20% tariff had been applied and we had a surprise bill for $10,000. It can easily take 180 days for many products to go from order, to on your doorstep and this tariff policy seems not to understand that."

Keep in mind that retail in particular is cutthroat and most stores operate on margins well below current tariff levels. I can assure you that a great deal of orders have been paused or cancelled over the past week (some freight estimates I've seen suggest a third of Asian-U.S. bound trade is now being paused or diverted to non-U.S. ports). And it will take months to get back to normal volume levels even if everything gets walked back.

We're also seeing layoffs and plant cancellations start in the U.S., such as a $300 million plastic recycling plant in Pennsylvania which got cancelled on Friday due to soaring building material costs.

The tariffs will only work in terms of creating new jobs in the U.S. if market participants believe the tariffs are permanent. To that point, as long as people keep talking about negotiating and trying to make a deal, no one is going to commit fresh capital to U.S. manufacturing given the tremendous uncertainty.

Here's Hart again:

If you’re building a new factory in the United States, your investment will alternate between maybe it will work, and catastrophic loss according to which way the tariffs and the wind blows.

No one is building factories right now, and no one is renting them, because there is no certainty that any of these tariffs will last.

How do I know? I built a factory in Austin, Texas in an industrial area. I cut its rent 40% two weeks ago and I can’t get a lick of interest from industrial renters. The tariffs have frozen business activity because no one wants to take a big risk dependent on a policy that may change next week.

In times of uncertainty, people spend less, pause commitments to future investments and look to raise cash. Even if the tariffs are walked back, we now have dramatically higher policy uncertainty which serves as friction to business activity.

---

I'd expect earnings estimates to get slashed over the next quarter. It seems optimistic to assume that S&P 500 corporate earnings will be above 2024 levels, so let's say $243 of earnings this year instead of the pre-tariff estimates of $270. $243 times a 20 multiple gets us 4,860 on the S&P 500, meaning the market is around fair value now. No need for a screaming rally even if political conditions improve.

And of course, in a downside scenario where tariffs persist for 6+ months, S&P earnings would be down significantly year-over-year and we'd probably see lower multiples as well. 17x earnings on, say, $220 of corporate earnings would get us an S&P 500 readout of 3,740 which would not be so ideal for buyers at today's prices.

And implicit here is the assumption that the market should continue to trade at an above-average multiple due to the higher quality of earnings. If the S&P 500 goes back to a more historically median multiple in the 14-16x range, the downside scenarios get worse. You could argue that if we are really rolling back globalization and returning to an economic system from the mid-1900s, that would lead to lower profit margins and thus lower multiples for U.S. stocks and in particular U.S. megacap tech stocks.

How's Mexico's Positioning Going Forward?

Mexico is one of the most interesting countries, geopolitically, out of the current situation. And the market's reaction speaks to that.

Mexican stocks shot up more than 5% on Thursday following the Liberation Day announcement as traders reacted to the news.

Then Mexico gave back the gains and more on Friday. Still, Mexico had a much better week than most peers:

For the week, Mexico was down just 3% in dollar terms. India was the other major country that bucked the trend, as it fell 4%. Meanwhile, the U.S., Europe, and China were all down about 9% and Japan slumped 11%.

The reason for this is that most of Mexico's international peers are getting hit with massive tariffs. It's not just China (54%), but also Vietnam (46%), Cambodia (49%), Bangladesh (37%), India (26%), and so on.

If you were a company that realized that China was no longer viable for exporting to the U.S. and moved your production to Vietnam, you are in nearly as bad a shape today as if you had just left your manufacturing in China.

Whereas, if you had moved to Mexico, you are now facing a tariff rate of zero percent (0%!) as long as your goods are USMCA-compliant. Will Mexico stay at a 0% tariff rate? Who knows. But it is likely to stay at a much lower rate than SE Asia given that the reciprocal tariff formula is based on the size of a country's trade surplus with the United States. Mexico has more equal trade with the U.S. than Southeast Asian countries and thus should be favored under this approach even if the USMCA framework doesn't hold up.

---

So, Mexico is a relative winner on the tariff front. In fact, a huge winner if the current tariff regime sticks as is.

On the other hand, Mexico sells 80% of its total exports to the United States.

If the United States is intent on going into a severe recession in order to reset its economic structure, Mexico is also going to get a serious recession. Mexico has built its economic and political system to serve as the affordable manufacturing arm of USA Inc. If USA Inc. is downsizing for the time being, Mexico is going to take blows from that as well.

Long story short, if the current tariffs hold, China, Vietnam and other countries in SE Asia are heading for a depression. Full stop.

Mexico, by contrast, will get a moderate-to-severe recession from the current economic order. Sure beats a depression!

But is it good for Mexican stocks? Not in the short-term. Eventually, yes. Crippling your biggest manufacturing competitors is nothing but upside for Mexico on a 5-10 year time horizon. But there will be challenges in the interim. The market's up-then-down reaction on Mexican stocks (as opposed to down and then down some more) was logical as Mexico has a large silver lining to this storm while much of the world has no positives whatsoever from current developments.

And How About The Rest of Latin America?

Latin America as a whole was a pocket of relative strength last week, and it wasn't just Mexico either:

In fact, Colombia was down just 2% on the week, Mexico down 3%, and Chile and Brazil both off around 5%. Only Argentina at -11% underperformed vs. the S&P 500 and Peru was off 9%, in-line with U.S. stocks.

This goes, happily enough, right in line with my calls from the LatAm 2025 outlook; Mexico and Colombia were the most obvious longs while Peru was a clear sell and Argentina was peaking in sentiment and set for a correction.

On that last point, Argentine local stocks have started taking on serious water:

You'll notice that Corporacion America Airports (NYSE:CAAP) (orange line) is the only one holding its ground recently. Funny enough, stock-picking actually matters.

The levered beta long Argentina camp is getting whipsawed at the moment, but CAAP stock is hanging tough given its much superior fundamentals and lower cyclical risk than most Argentinian equities. It was easy riding the Milei wave higher regardless of what local stocks you picked. Now when more challenging conditions hit, however, we see which Argentine stocks have underlying support, and so far CAAP is showing tremendous relative strength.

I expect that Argentina will get back on track and equities there to rally back toward the highs. Milei's government is continuing the perform reasonably well. And Milei is, arguably, Trump's favorite foreign president at the moment. It's not implausible to think Argentina is a relative winner out of the current disruption and could pop on any headlines around strategic deals for Argentine lithium, rare earths, or whatnot as the U.S. juggles supply chains around. In other words, I am happy to keep holding CAAP shares here. Argentina should perform relatively well and CAAP will lead the rebound there.

---

On to Colombia, which was one of the best-performing equity markets last week. Why? I'm not entirely sure. I can make the long-term bullish argument and the 2026 Colombian election argument, but neither of those were particularly relevant to last week's affairs.

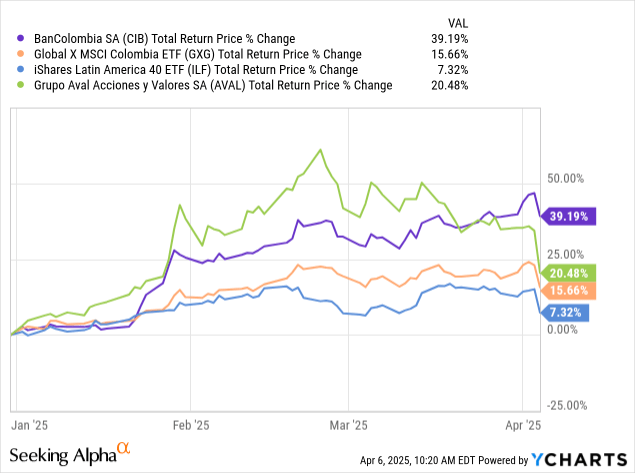

However, Bancolombia (NYSE:CIB) in particular continues to trade like it was just shot out of a cannon:

That's right, Bancolombia (counting the $3.71/share dividend they just paid us last month) is up 39% year-to-date. That's compared to a 20% gain for Colombian bank peer Grupo Aval (NYSE:AVAL), a 16% move in the Colombian ETF, and a 7% rally in the Latin America 40 ETF year-to-date.

I love the Colombia investment theme long-term, and Bancolombia is an excellent operator. But even I struggle to maintain high levels of bullishness after a 40% 3-month rally while the global economy barrels into a serious recession.

That's doubly true considering that the price of WTI crude oil just plunged from $72 last week to $60 now. Oil makes up about half of Colombian exports, so that's a cool 15% chunk it just lost of its key export. You can argue at the margins that Colombia is a relative winner since there will only be 10% tariffs on its coffee, cocoa, and other such agricultural goods as opposed to 30%+ tariffs on those items from a lot of its competitors. But I think that's splitting hairs when Colombia's main export is collapsing in value.

The Colombian Peso, after months of steadiness, puked lower on Friday, falling more than 3% against the U.S. Dollar. The Colombian central bank usually manages volatility and doesn't let the currency drop more than 1-1.5% per session. When they allow a big drop like this, it's usually indicative of heavy selling pressure and a situation where the currency will gradually continue to decline for a while.

Off the top of my head, I don't remember any other 3% one-day declines for the Col. Peso since 2023. All this to say that locals see oil plummeting and are heading to dollars for safety. Against this backdrop, I'm not convinced of the merits in holding the entirety of my Bancolombia position here.

It pains me, but I am a seller for the aggressive portfolio on CIB stock today.

Counting dividends, it leaves at nearly a 70% gain for our portfolio. I was hoping to hold through the election and get a triple on the position. And maybe that would still be the right play.

But I remember what happened in Colombia in 2020 (I was living here after all) the last time oil went no-bid.

CIB stock dropped from $55 to $13 in three months. I had sold half my CIB shares at $50 but obviously should have sold more with the benefit of hindsight.

Given this context, I feel compelled to lock in at least some of my large gains on the Bancolombia position.

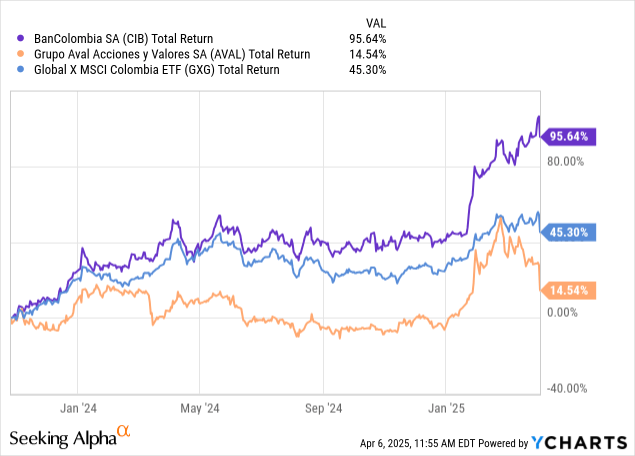

I intend to revisit this once the current situation settles down a bit. Aval (the other listed Colombian bank) is back to dramatically underperforming Bancolombia, so there's a case for rotating from CIB stock to AVAL stock now. Here's the returns for both along with the Colombia ETF over the past 18 months:

That said, I'm just a seller on CIB now.

Hopefully we can redeploy those funds into AVAL down another 15-25% if things continue to worsen over the coming weeks.

China: Winner, Loser, Or Somewhere In The Middle?

I see a lot of people on Twitter claiming that China is a winner out of the current tariff mess. I wholeheartedly disagree.

The China bulls are thinking that the United States is destroying its global credibility and that countries will no longer want to rely on the U.S. as a key trade partner. Fair enough. Understandable line of reasoning.

But can countries really pivot to China? (And granted, much of Sub-Saharan Africa and very poor parts of LatAm like Bolivia/Nicaragua/etc. have built close ties to China)

But will you see bigger economies like say, Poland, Singapore, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, or Mexico pivoting to China? Almost certainly not.

In theory, a country like Saudi Arabia could suddenly decide to entirely throw its lot in with China.

Here's the issue(s). For one, China's economy is already dreadfully weak. It never emerged from COVID-19 and was trending from bad to worse in 2024 even prior to Trump's election. There's a reason that the only reason Chinese stocks rallied in recent quarters was rumors of a record stimulus package out of the CCP.

But stimulus only gets you so far when you are already massive indebted. China has (by far) the highest total debts to GDP across its corporate, local, and national governments. The government and financial institutions have spent hundreds of billions of dollars on "investments" of dubious merit such as ghost cities, high-speed rail to nowhere, and massive bridges in rural hinterlands.

China has kept up the appearances of being a functional economy thanks to tremendous malinvestment of funds in unneeded projects. This sort of activity would be impossible in a democratic society, but one-party rule makes it easier for this sort of thing to persist for a while (see also: Wild spending on white elephant projects in the Middle East with oil money).

But even for an authoritarian government, eventually they run out of ability to keep borrowing to extend and pretend. There's been a great deal of discussion elsewhere about how much longer China can avoid a debt-driven collapse of its financial system, but for the sake of brevity, let's just say that they are on a weak footing going into the current crisis.

Now, their top source of hard funds just hit them with a 54% tariff. That is going to collapse their exports to the U.S. along with close U.S. allies like Mexico that are also slapping China with fresh tariffs and non-tariff trade restrictions. This is before we get to matters such as the U.S. prohibiting its allies from buying national security-related materials from China and so on.

The Chinese model was built around two guiding principles: It had an unceasing supply of new labor at low prices, and it could keep sucking up dollars (and euros, pounds, etc.) from the rest of the world indefinitely. It has managed both its labor supply and its currency (high levels of capital controls, prohibitions on foreign investments in the country, etc.) to keep this artifice standing.

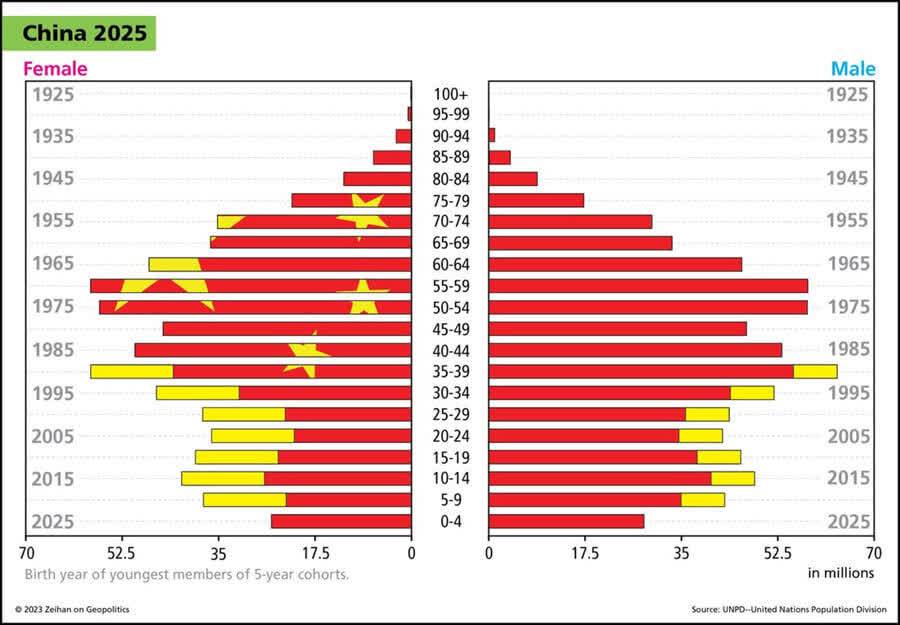

China is doomed over the longer-term due to demographics. Here is a table showing China's demographic pyramid, both as reported, and with yellow bars indicating more likely true figures than the massaged data from China's demographic bureau.

According to official Chinese statistics, there are barely half as many children as there people in prime working age segments such as 35-39 and 50-54. And when you adjust for the fact that China's statistics are notoriously unreliable and use independent Western estimates of their true population data (removing the yellow bars), things look bleaker yet.

In any case, China isn't going to have the bodies available to be the same economic force in the world 20 years from now that it has today. Just look at the massive grouping of 50-60 year olds they have now and how few 10-19 year olds there are coming up to replace them. China is a dead end as far as economic growth goes. Economic growth is population growth + productivity gains, all else held equal. Population collapse combined with lack of access to technology for productivity gains due to US export bans equals economic morass if not collapse.

The long-term best case outcome for China is that it follows Japan's circa 1990 path and goes quietly into that good night. Think no returns from the Chinese stock market for the next 30 years as its population gradually moves from factories to nursing homes with no youthful generation to pick up the slack. As always, there can be short-term rallies. We did great with JD.com call options last year. I'm talking long-term here.

It makes no sense for unaligned countries to pivot to China whose population will be geriatric a generation from now.

That's even before considering that 1. China's economic system is built on mountains of debt and malinvestment and 2. They are a terrible counterparty for business because you can't freely buy their stocks or currency and they have minimal rule of law protections for foreigners.

Say what you will about U.S. governance and politics over the past decade (it has some problems, to put it mildly), pivoting from the U.S. to China is going from bad to much worse.

And indeed, we see that in the response to the tariffs:

China has no bloc of meaningful countries to hold it up. Its friends are largely other countries that are excluded from the world order such as Russia, Iran, North Korea, and Cuba.

Could the U.S. burn so much goodwill that it also becomes unreliable as a partner and ally and folks feel the need to turn elsewhere? Sure, it's possible.

In that event, I'd see the European Union (for all its faults) or some other coalition of Western like-minded countries being the central building block of a post-U.S. economic order. It's just not plausible to think the world's reserve currency and economic center would be a country that has a rapidly dying population, terrible rule of law, and a currency that is difficult for foreigners to own or invest in. What kind of reserve currency would the Yuan be when the Chinese government places massive barriers to us foreigners even buying it in the first place?

Let's not overthink this. China built its economic model on exporting. Its largest export market just hit it with a 54% tariff while putting a 0% tariff on the U.S.' two other largest sources of imports (Canada and Mexico). This is bad for China.

How High Can Bond Prices Go?

Yields on 10-year U.S. government bonds dipped below 4% last week after an extended run in the 4-5% range (as always, falling yields means higher bond prices. If you own bonds, you want yields down as it means price up):

Bond bulls were celebrating on Twitter, though I see little reason for the excitement. Yields are still above where they were last August during the Japanese flash crash, to say nothing of where we were in the 2022 bear market or during the COVID-19 crisis.

Members of the Trump Administration have pointed to long-term interest rates as a fulcrum around which they are basing economic policy. There's a belief that if long-term interest rates come down, this will allow the government to refinance a great deal of its debt at lower yields. This, in turn, would reduce the government's interest expense and help improve the fiscal picture.

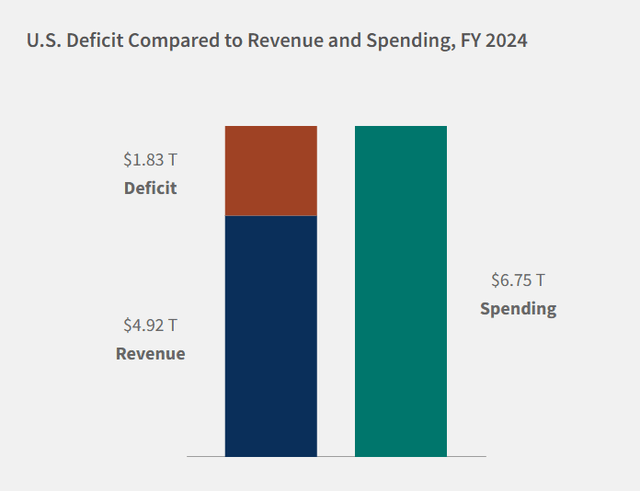

Interest on the U.S. national debt came in at $882 billion last year, which was the largest tally in a single year to-date. This comes both as interest rates have gone up and also due to the size of the overall national debt increasing. The government spent about $6.8 trillion last year, meaning that interest is running at about 13% of the total pie.

The government's total deficit last year was $1.8 trillion. Even if interest expense went to zero, that would still only eliminate half of the deficit. Either taxes have to go up or spending on other items must also be reduced. Still, the interest expense at $0.9 trillion is a major component of spending, so if it could be significantly reduced, that would make the rest of the equation easier to solve.

There are two obvious sticking points here.

The first is that we had an extended period of exceptionally low interest rates, meaning that, on average, the U.S. government already is not paying much on its debt. The precise blended interest rate across its debts was 3.3% last year.

2-year government bonds are yielding 3.6% as of this writing, 10-years are at 4.0%, and 30-years are at 4.5%. All of these, you'll note, are above 3.3% by a significant degree. There's no part on the curve where the government can refinance and meaningfully reduce interest expenses yet. In other words, the mild drop in interest rates we've seen in 2025 to-date is nothing as far as addressing the federal budget goes.

Some people believe the Trump Administration is going to keep pushing forward on the tariffs and stock market down talk in order to get interest rates lower.

Trump, in fact, retweeted (ahem, retruthed) a post saying he is causing a stock market decline in order to get rates down:

If you take this line of reasoning at face value, interest rates need to go down a lot more before Trump will be satisfied, bonds will be refinanced, and then the Treasury can proceed to the next part of its plan.

When Trump himself along with several of his staffers are explicitly saying that they don't care if stocks go down and they will move heaven and earth to get bonds prices up, I want to own some bonds. In other words, I'm not even thinking about starting to sell into the micro-pop we've gotten in bonds so far.

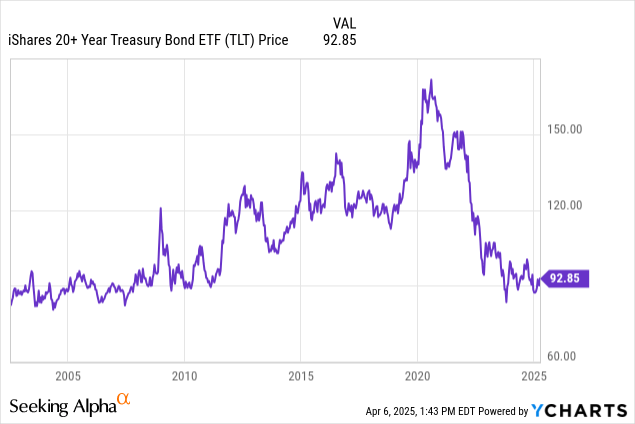

Here's the long-term chart of TLT, the benchmark ETF for longer-duration U.S. government bonds:

You got a 50% pop for the Great Financial Crisis, a 50% pop for the European crisis of the early 2010s, and another 50% rally in late 2019/early 2020.

TLT should be back to $120, if not higher, if and when people believe that globalization is ending, a major worldwide recession looms, and that equities will be in a bear market for a while.

I'm not saying that is a guaranteed outcome by any means.

But if you believe the bearish view on stocks right now, then you should also be mega bullish bonds here. And if you're not super bearish on stocks, bonds are still good hedge/protection. TLT/EDV/etc. aren't that far from their 20-year lows. Downside for long bonds is 10-15% from here in the intermediate-term if Trump walks back the tariffs and the world economy normalizes quickly. Whereas upside is at least 40% from here and quite possibly a lot more (again, measuring in TLT -- the move in EDV and other more extended durations will be even larger) if we get the recession scenario.

---

Keep in mind that a bond issuance has two parties. There's the issuer, in this case the U.S. federal government, whose intent is clear. It wants to roll over debt at a low rate so that interest expenses don't gobble up all the funding that is supposed to go to pay for the military, Social Security, Medicare, etc.

But ask yourself: Who is buying a U.S. government bond at a 2% yield, 1% yield, etc.? Why would they do that?

The buyers do that because they think the global economy is in a world of hurt, there won't be any inflation, and they are worried about potential mass corporate bankruptcies (which keeps people out of both stocks and corporate bonds, thus giving governments ultra-cheap funding).

If you are committed to low interest rates at the expense of everything else, having an economic depression is the best way to achieve your aim. Keep in mind that there was widespread deflation during the 1930s. CPI fell 27% between 1929 and 1933!

We're rerunning 1930s tariffs, are we going to get 1930s deflation? Those of us with economics degrees are blessed to be alive at a time to see such an audacious experiment in our field.

In any case, government bonds are the ultimate safe haven in a storm. Cash is king, and government bonds are the safest kind of cash within the financial system (along with CDs and anything else with a federal backstop). In other words, this is the ideal time to be loading up on bonds for insurance. The question is not whether to sell bonds here, the question is whether to add to existing bond positions. Unless we get a total 180 on tariffs, bonds are going higher. A lot higher.

Are Tariffs Inflationary Or Deflationary?

Deflationary.

But Ian, tariffs make prices go up. That's obviously inflationary, right?

In the very very short-term, sure.

But the inflation only sticks if people actually have the money to pay the new higher prices in perpetuity. If people don't see an increase in their income, they will simply buy less units of stuff to reflect the higher price.

For example, a new car costs $30,000 now. Thanks to the tariffs, the automaker will have to charge $40,000 for it six months from now to earn the same profit margin. So that's 33% inflation, right? Not really. Because what happens to sales? Before if you sold 1 million units at $30k, now you might only sell 600,000 units at $40k. Total revenues were essentially flat, but the amount of money going to the auto producer drops (since a big chunk of that $40k now goes to the government for its tariff tax instead of being in your profit margin).

What happens when the automaker earns less profit? It fires employees. Those ex employees, in turn have far less money to consume iPhones, gym clothes, dishwashers, golf clubs, and everything else that was imported.

Repeat this cycle of layoffs and consumption cuts a couple of times and what do you end up with?

A massive economic bust, that's what.

And what do companies do when they have way too much inventory and can't sell it?

They slash prices.

There, that is how you square the circle.

---

Tariffs will initially raise prices. If there is some mechanism to give people more money with which to consume, then you will see the higher prices stick and inflation surge.

But there's no magical money spigot this time around. Central banks have tightened monetary policy and aren't cutting rates aggressively just yet (unlike 2020 when capital was free). The U.S. federal government is currently on an austerity kick, whereas it was mailing people checks in 2020. And bank credit will decrease as well (banks drive money supply at the margins) as they see current economic uncertainty and call in loans, cut credit limits, and otherwise tighten the screws.

At the end of the day, inflation is primarily a money supply problem. Create too much money, and prices go up.

Tariffs are a tax. Taxes don't create money. They don't add to any wage/price spiral in the economy. When taxes are increased, absent any stimulus in other areas, the economy slows and prices fall. These tariffs will be deflationary if they stick for any meaningful period of time.

Buy The Dip On Oil?

Oil dropped to $40/barrel in 2015 simply due to too much U.S. drilling -- no macro overhang or anything. Oil dropped to negative prices in March 2020 when the world economy froze up there for a minute. Color me skeptical that a 20% dip on oil now is a back-up-the-truck buying opportunity.

We were fortunate enough to exit our oil call long positions in the aggressive portfolio near the multi-year highs when Russia invaded Ukraine. I've largely stayed away from oil since then, particularly since we get exposure to it via other means (i.e. long LatAm stocks such as Colombian names).

Most of the major oil companies were still trading reasonably strongly up until this week. Suncor (NYSE:SU), a favorite of mine, was just 5% from its 52-week highs up until Thursday. That seems generous given the tariff uncertainty with Canada/US, slowing economy, and soft oil prices even prior to the recent decline. Other high-quality oil names have fallen farther; Canadian Natural Resources (NYSE:CNQ) is at 52-week lows for example. But earnings will be coming down at least moderately if not dramatically and I don't see a rush to buy there. There's a lot of stuff selling off right now that is not too cyclical and not that exposed to tariffs.

Trying to trade a bounce by buying oil seems overly complicated. Tariffs are deflationary, not inflationary. There's no rush to be buying inflation-sensitive assets like oil here.

So, Ian, Markets Up Or Down From Here?

At one point on Sunday evening, S&P 500 futures were down more than 14% over a three-day period, making it the fastest market crash since 1987 as measured over a 3-day span. Pretty incredible to drop more quickly than in 2008 or 2020.

Even in big bear markets (which this may or may not be, only time will tell), you get large countertrend moves as shorts take profits and traders try to find attractive entry points.

Put another way, you rarely are making a good move selling (or selling short) after an immediate double-digit decline. There will be rallies, and if you feel the need to lighten up on positions, sell into those. There's no need to panic dump stuff today.

Longer-term, I think forward returns on the S&P 500 still aren't that attractive.

The outlook is better than at S&P 6000, where a reasonable estimate would suggest that the market was likely to produce a negative total real return over the next five years.

We're at least back to (modestly) inflation-beating expected returns from current prices. But this is hardly a fire sale of U.S. equities at today's levels, especially if globalization is really being rolled back and U.S. corporate profit margins go into structural decline going forward.

I've been sitting on a ton of cash in the aggressive portfolio since 2023. That's not a preferred position for me -- I like being very long, often on margin if the opportunities arise. But there was a limit to how much capital I was going to commit to emerging markets for that portfolio and there simply wasn't much worth swinging at in U.S. markets over the past year.

Hopefully that will change given the current uncertainty. The 52-week low list is finally filling up with some quality names and this seems like a reasonable place to start bargain-shopping on your preferred companies. If the U.S. market drifts down below the 4,500 level on the S&P 500 in coming weeks, I intend to deploy most of the cash in the aggressive portfolio going forward.

Fantastic work, Ian. Sounds like you like CAAP in spite of the Argy selloff, whereas no mention of the Mexican airport operators...you think they will catch the US recession cold as well (makes sense if primary driver for OMAB is US/mex trade)?

Jet fuel about to get a lot cheaper and I can see a lot of holiday travel between Europe and LatAm this year.