The Petro Panic: Colombia Has Crashed, Is It Investable Now?

Now down 80%, are Colombian stocks cheap enough to justify the risk?

Summary

Colombian assets have slumped in recent months to historically low valuations.

That's because the country elected its first left-wing president of the modern era, and investors are reassessing whether the country will remain business-friendly.

I break down the bull and bear cases for Colombian assets.

My verdict on the macro situation, and individual Colombian equities including Ecopetrol, Bancolombia, Aval, and Tecnoglass.

I've been putting off writing this report for awhile for two reasons. One, I'm a Colombian resident and thus have significant personal feelings about our political and economic outlook. I've lived here since 2018, my wife is Colombian, and both my kids are dual Colombian-American citizens.

And also, the state of play remains very much unsettled. I'd much rather give you a decisive "this is what's going to happen" article, but there simply are too many unknowns to forecast with confidence today.

That said, valuations have now reached such absurdly low levels for Colombian assets that I feel compelled to update on the situation. There's also sentiment indicators that often mark a bottom. Blackrock just shut down its Colombia ETF. And Zerohedge just had a popular tweet about our plight:

When ETFs are closing down and the permabears are getting excited, there's often a buying opportunity. I don't have all the answers, but we can at least assess the Colombian situation and make investment decisions accordingly.

The Quick Bull Case

Two words: Deep value.

Colombian stocks are now down 80% (in dollar terms) since their 2012 peak:

The index hasn't changed much in composition, either. It's largely the same companies, with similar profitability today as it was in 2012. Except, before, they were trading at 15 P/E multiples and now they are at 4x P/E multiples.

Ecopetrol (EC), the state-managed oil company, is our largest listed company. Despite reporting record profits at the moment, shares are not far from their all-time lows and trade at 3.6x earnings:

The 23% dividend yield certainly catches some eyeballs as well.

After the oil company, the next most prominent Colombian assets are the banks. Three banking firms -- Bancolombia, Aval, and Davivienda, make up 70% of the entire national banking market. These have traditionally been sheltered from competition and earn abnormally high fees and net interest margins, making them some of the most profitable banks in South America.

Two of these firms, Bancolombia (CIB) and Aval (AVAL) are listed on the New York Stock Exchange. AVAL only went public in the U.S. in 2014, so a long-term chart is not available. CIB, however, has been quoted in New York since 1995.

Bancolombia, including dividends, is up about 500% since its U.S. IPO. However, there was a great deal of volatility along the way. Shares dropped to a buck during the 2001 Latin American default spree (Colombia didn't ultimately go bust, but most of its neighbors did). Then Bancolombia shares went up 50x between 2001 and 2012.

Shares were, incredibly enough, up 100% in 2003, up another 100% in 2004, and up 100% again in 2005 for good measure. A 10-bagger in three years.

Bancolombia also was one of the few banks to remain profitable in 2008/9 financial crisis and had already soared to new all-time highs by the beginning of 2010. Additionally, Colombia was the world's single best-performing investable emerging market in the 2000s decade.

So, this sort of jaw-dropping volatility for Colombia is normal. It's not unprecedented that Colombian stocks are currently off 80% from their highs. It also wouldn't be surprising if they rally 500-1,000% during the next bull market.

Bancolombia, like Ecopetrol, is currently at 4x earnings. It's also going for just 0.7x book value, which is a rather undemanding price for a firm that has traditionally averaged a 15% return on equity. Shares also pay a 10% dividend yield at the moment.

The Quick Bear Case

Buying stocks at these sorts of valuations should be a home run, right? Anyone that invested in Colombian stocks or bought property in Medellin in 2001 is now living on a yacht. Won't the same thing happen this time around?

Perhaps. But there are real risks to consider.

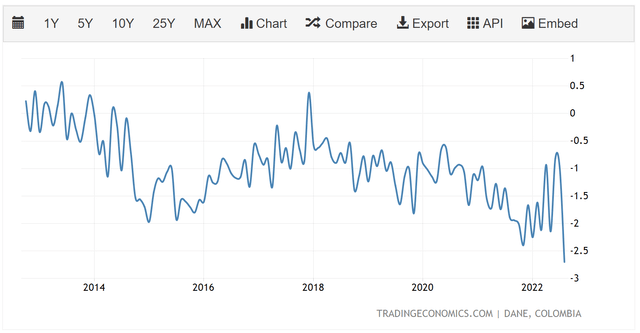

We'll get to the new president in a minute. But first, there's important context to consider. For example, Colombia's trade balance:

Chart in billions of dollars per month.

Traditionally, Colombia has run a balanced import/export policy with no trade surplus or deficit. This changed in 2014 when the price of oil plummeted. Colombia generally earns around half its foreign exchange dollars from petroleum, and thus having oil go from $100 to $50 was very bad news. The trade deficit eventually stabilized at around $1 billion per month.

With a Colombian GDP of $300 billion, a $12 billion annual trade deficit is around 4% of GDP. That's a significant sum but not devasting.

However, the trade deficit has soared in size in 2022, often topping $2 billion per month. That would put it closer to 8% of GDP, which is a significantly bigger issue. Colombia imports a sizable amount of its food, along with goods such as consumer electronics where there is minimal domestic manufacturing capacity. These costs have soared this year with inflation and the falling value of the Colombian Peso.

In addition to the trade deficit, the government typically runs a small budget deficit as well. Again, this hasn't normally been a problem. But falling revenues from the oil sector have added some pressure and now there is less certainty around the government's fiscal responsibility with the change in governance.

Long story short, Colombia faces twin deficits that foreigners need to finance for the foreseeable future. This is important to realize, since the newly-elected president, Gustavo Petro, is taking the opposite approach, instead antagonizing foreigners and causing investors to rapidly pull money out of the country.

---

I know trade deficits are boring economist talk. But it matters greatly in this case because Colombia needs dollars from one source or another to make it to 2026 (when Petro's term is up and there will be a new president, as there is a one-term limit for leaders in Colombia).

Assuming nothing structural changes, Colombian assets are a home run buy here with 5-10x upside once a more business-friendly government regains power. However, Colombia first has to fund itself for almost four years through a time when the President is actively causing investors to sell Colombian assets. Meanwhile the easiest solution to get more dollars -- sell ample oil and coal reserves to foreigners -- is also being rejected.

It's easy and understandable for bulls to say "But Petro hasn't actually done anything and his political power/mandate is weak." 100% true! However, mere inaction -- running large deficits while blocking any feasible path for dollars to make it to Colombia -- could destabilize the economy and banking sector regardless.

Any bull case for Colombia inherently assumes that the current economic and political structures remain in place. Someone asked me whether Colombia was priced closer to Venezuela or Argentina.

And that's the wrong question. Because if either of those options is on the table, Colombia is already done as a serious investable country.

Consider CDS spreads:

Colombia's default premium is still roughly in-line with Brazil's and not entirely out of league with the higher-quality countries in LatAm, namely Mexico, Chile, and Peru.

Argentina's CDS, by contrast, often trade above 1,000 points and Venezuela doesn't have a functioning bond market at all.

Colombia has also had a stable currency since the turn of the century. Over a 15-year period, between 2003 and 2018, the Peso was flat against the dollar. And it actually rose substantially at one point, surging 35% between 2003 and 2011:

As recently as this summer, prior to the presidential election, the Peso was still at 4,000. Not bad given the huge run-up in the Dollar.

The Colombian Central Bank is viewed as one of the most competent and independent among emerging markets, and has done a fine job of fighting inflation over the past 20 years. On top of that, the string of conservative governments in Colombia have practiced austerity when needed and not been afraid to raise taxes to maintain a sound budget.

Since June, however, as Petro won the presidency, the Peso has slumped from 3,800 to 4,900 in virtually a straight line:

Some of this can be explained by the general strength of the U.S. Dollar, but it's still a huge move and far out of line with other regional currencies. The Mexican Peso, for example, is flat for the year against the U.S. Dollar.

Why is the Colombian Peso tanking. Let's count the reasons. The new Petro government:

Threatened to institute capital controls to keep money from leaving the country.

Is planning tax hikes on the wealthy.

Has blocked all new issuance of oil, gas, and mining permits.

Wants to break up the big banks.

Has urged the Central Bank to stop raising interest rates, infringing on its historical monetary independence.

Has recently urged Colombians to do their patriotic duty and keep money in Colombia (a universal red flag in LatAm -- see the corralitos in Argentina).

Has blamed a U.S. conspiracy for tanking Latin American economies.

Is reestablishing normal foreign relations with Venezuela.

How much of Petro's talk will become policy?

That's the million-dollar question. Petro's cabinet has several moderates in it, including the finance minister, Jose Ocampo. Whenever Petro or another cabinet member makes an extreme statement, the finance minister has always walked it back or put it in a more market-friendly context.

To give one example, the mining minister said flatly that there won't be any new mines or oil exploration permits during this government. The finance minister immediately tweeted that no final decision had been made on the matter yet. For another, Ocampo immediately contradicted Petro saying Colombia was not considering capital controls after the president had mentioned the possibility. This sort of open squabbling among members of the government has been unusual and speaks to the lack of clear coherence across its agenda.

Petro was elected with a significant lack of support. He failed to win in the first round of voting outright and only narrowly won in the run-off vote over a previously completely unknown outsider. Petro's party fell far short of majorities in Congress and has had to build a coalition with moderate parties to get a majority bloc. This will allow Petro to pass some legislation, but likely hinder him from pursuing more radical steps. The Supreme Court also tends to be conservative, and the perception is that Petro doesn't have strong support among the military either.

This seems similar to what happened in Peru, where it elected a full-on self-proclaimed Marxist peasant in 2021. That president struggled to fill his cabinet with capable ministers and was immediately struck with corruption scandals and popular uprisings. It now appears the extreme left-wing president will be impeached, and Peruvian capital markets have fully recovered from the 2021 communism scare. This sort of event is not uncommon in Latin America.

All this to say that if you were betting, you'd wager on Colombia's democratic institutions holding up over the next four years. The Petro government doesn't seem to be especially powerful or united, and its approval rating has already dipped 20 points since inauguration. The most probable outcome seems to be a pivot to the center, particularly as financial markets place constraints on Colombia's budget.

That said, it's far from a sure thing that we'll get that approach. Much of the pro-business wing of things is being held up by one man, the finance minister. If he were fired or resigns, that would be a major negative shock to Colombian assets. As discussed, Colombia is running sizable deficits right now, so there needs to be a competent and respected figure that can talk to international bondholders.

---

My personal view is that Colombian assets are now so ridiculously priced that it's worth taking a long position on the Peso, Colombian stocks, or local real estate. I fully acknowledge there's a significant chance of everything going to hell in a handbasket. I'd call it 25% now if you forced me to stick a precise number on it. And Colombian financial assets could quite possibly be worth $0.00 in that worst case scenario. So let's not sugarcoat anything in terms of potential downside.

However, the most likely outcome is still that Colombia muddles through the current period and assets recover in value with the next president. What sort of bargains are we getting today?

To give an idea of just how absurdly cheap Colombia is, look at a cost of living comparison. For the sake of this exercise, I'll use two mid-tier cities: Denver, Colorado, and Bucaramanga, Colombia. Denver is the United States' largest mountain city and has a solid but not spectacular economy. Bucaramanga is a million-person urban area in Colombia that is its country's nicest mountain city, and isn't overrun with foreigners. As such, Bucaramanga prices are reflective of what Colombians pay for things, as opposed to the inflated prices you see in the tourist neighborhoods of Medellin and Cartagena.

So how do things look when we compare the Andes to the Rockies? Bucaramanga is about 80% cheaper across the board. You would need $6,100/month of income in Denver to buy the same goods and services you get for $1,100 in Bucaramanga:

Some notable differences. Private preschool costs $1,500 a month in Denver versus $100 in Bucaramanga. A downtown apartment costs $3,300/month in Denver versus $275 in Bucaramanga. High-speed internet costs $70/month in Denver versus $15 in Colombia. And a three-course sit-down meal for two people costs $70 in Denver versus $12 in Bucaramanga.

Of course, things should be cheaper in Colombia since wages are much less. But should they be 80% cheaper? Probably not. Historically, LatAm has been closer to a 50% discount (i.e. double your purchasing power moving here). Widely followed popular indicators such as the Big Mac Index also suggest the Colombian Peso is at a record level of undervaluation, both in absolute terms and against other Latin American countries.

The inverse here is also worth considering. If you have a median Denver level income... call it $72,000 a year... and spend it in Colombia, you are getting a mid-six figures standard of living. But that's a topic for another post.

I could keep rambling, but the point here is that there's no fundamental reason for the Peso to be anywhere near 5,000 to the dollar. If Colombia had a more orthodox president and economic policy at the moment, the Peso would strengthen 25-33% almost immediately. The drop is entirely based on fear and uncertainty toward the future.

If the Peso returns to where it was before Petro was elected, along with Bancolombia trading at an 8x instead of 4x P/E ratio, you would have a $72 stock compared to its $25 price today. That's assuming no earnings growth either, just on current figures. Even assigning a 25% chance of all Colombian assets going to zero, risk/reward is still tremendous.

So what to buy and what to avoid? Grab a cup of coffee (Colombian please, we can use the support right now) and we’ll jump into the second half of this report.

Specific Colombian Stock Analysis

With the lay of the land established, let's dive into the specific Colombian traded stocks.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ian’s Insider Corner to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.